Paleontology is an unloved branch of naturalism in Rhode Island. As of 2025, the only paleontological work being done here is quaternary palaeoclimatological work. Rhode Island lacks almost any Mesozoic formations, with the exception of Cretaceous era Raritan formation clays on Block Island. On Block Island there is some Cenozoic material, but the Paleozooic dominates the available fossil bearing localities. On Conanicut Island in Jamestown, there is some Cambrian material, but by far the most common fossils in Rhode Island are Carboniferous era. This era is also what most fossil hunters in the state are looking for, including the Author/Artist Steve Emma, who’s personal guidance and book were essential to building my knowledge of Rhode Island’s Paleontology.

History of Rhode Island Paleontology.

1880s

The earliest known western paleontological work in Rhode Island was done by Reverend Edgar F. Clark in the 1880’s, who was seemingly based in Pawtucket. He was the contemporary of two other fossil hunters, both young at the time, Herbert Arthur Schofield, who was around 8-11 at the time of collecting most of these fossils, and Frederic Poole Gorham, who would have been 17-21 (Herbert Arthur Scofield (1881–1939).” FamilySearch, Frederic Poole Gorham (1871–1933).” FamilySearch). At the more professional level, the then Brown Professor Alpheus S. Packard was being given fossils by the young men and the Reverend, who gave them to the writer of Rhode Island’s earliest paleontological report, Paleontologist and Entomologist Samuel Hubbard Scudder. The first report, dealing exclusively with insects, Insect Fauna of the Rhode Island Coal Field, 1893, lists the following localities and genera (Scudder, Samuel Hubbard. Insect Fauna of the Rhode Island Coal Field. U.S. Geological Survey, Bulletin 101, 1893)

| Town | Locality | Taxon | Finder |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bristol | General | Mylacris packardii | Clark |

| Cranston | Fenners Ledge | Etoblatina sp. | Gorham & Schofield |

| Cranston | Lockonosett Mine | Rhaphidopsis diversipenna | Clark |

| East Providence | General | Etoblatina scholfeildi | Schofield |

| East Providence | Kettle Point | Etoblattina exilis | Schofield |

| East Providence | Silver Spring | Etoblatina sp. | Schofield |

| East Providence | Silver Spring | Gerrablatina fraterna | Schofield |

| East Providence | Silver Spring | Paralogus aeschnoides | Gorham |

| Pawtucket | General | Anthracomartus woodruffi | Clark |

| Pawtucket | General | Etoblatina clarkii | Clark |

| Pawtucket | General | Etoblatina gorhami | Gorham |

| Pawtucket | General | Etoblatina illustris | Clark |

| Pawtucket | General | Etoblatina requia | Schofield |

| Pawtucket | General | Etoblatina sp. | Schofield |

| Pawtucket | General | Gerrablatina sculptularis | Schofield |

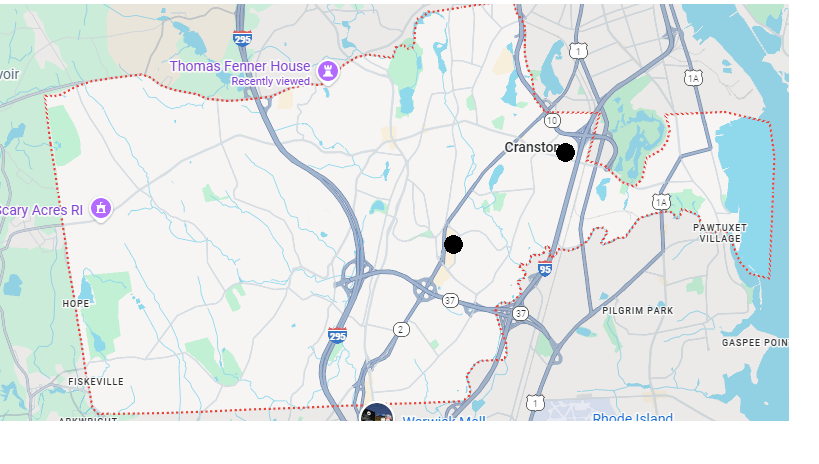

For the entirety of the state, that looks like this, with dots representing quantity of genera per town.

For the two towns with localities named, East Providence and Cranston, the localities are placed accurately

In Cranston, the two localties are under what is now Garden City center to the South, and the second is a still exposed ledge next to an Aldis on 1015 Cranston Street, information I would not have known if not for the great website Strange New England, which is very much worth checking out (https://www.strange-new-england.com/2017/04/13/deadmans-cave/#more-918)

In East Providence, Kettle Point still remains an accessible location, however Silver Spring no longer exists, though it may be on the location of Silver Spring Elementary School

1914

In 1914, the tunnel underneath College Hill was constructed for the sake of a trolley system, and an enormous amount of fill was removed. The fill was rich in more Narragansett formation Carboniferous era fossils, including an amphibian trackway.